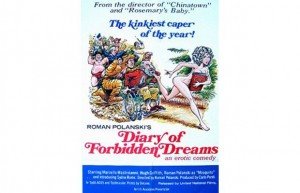

Diary of Forbidden Dreams

What’s being called Diary of Forbidden Dreams or simply Forbidden Dreams in its current run is actually Roman Polanski’s 1972 opus What?, being released in the U.S. for the first time to cash in on the director’s recent notoriety.

Like Dance of the Vampires, which he made five years earlier and which also suffered a ridiculously obvious retitling for its American release, What?

looks like a film on which the director emphatically did not have final cut. The English-language version, at least—dubbed by predominantly British voices and edited by people with British names—looks like less than what Polanski must have intended. Still, judging from the evidence (which is all one can do), it’s hard to believe there was much good in the film to begin with.

It’s a venture into the surreal world of dreams—erotic, paranoiac, recurrent—symbolized in a Romanesque villa where a lot of curious people come and go with no apparent purpose.

The heroine (Sydne Rome) stumbles into the place while trying to escape from a trio of rapists who have been thrown into a momentary muddle by the attempt of one of their number to sodomize another during the rape. In succession she encounters: distinctly absentminded servants; Alex, a shy ex-pimp with a taste for s&m (Marcello Mastroianni); some rowdy youths who discuss and perform sex with the same detached agility that characterizes their PingPong-playing; a violent, pugnacious short guy (Polanski himself) who enjoys brandishing a harpoon gun; a wayward priest; a pair of American tourists; a pair of German lesbians; a severe nurse who reads Nietzsche while administering digitalis to the villa’s aged master, Joseph Noblart (Hugh Griffith); and a self-pitying arthritic pianist (Romolo Valli) who plays Mozart divinely. The pastiche of characters and situations evokes Alice in Wonderland (walking on the beach the heroine tells Alex, “I’m Scorpio—what sign are you?” to which he replies, after a befuddled moment, “Lobster”); but this heroine’s well-meaning, impossible naïveté puts her well behind Alice.