“Metropolis, 1984”

“Between the mind that plans and the hands that build there must be a Mediator, and this must be the heart.”

Metropolis, 1984 (Brigitte Helm), Cinecom

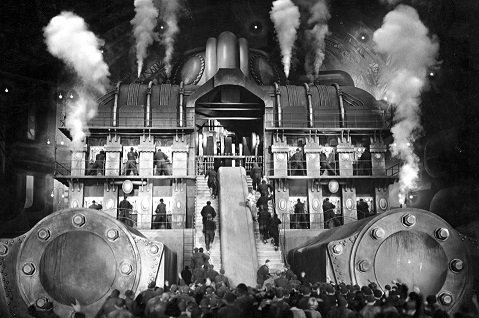

We start with an explanation of why Giorgio Moroder did what he did; that is to take a print of Fritz Lang’s Metropolis, and then to add previously missing footage and photographs, affix his newly-produced musical score, and then release the result. A montage of dangerous-looking machinery turning joined with text describing the pleasures and privilege of the “chosen sons” in the elevated city of Metropolis begins the movie. We are shown that the benefits of these few are the result of the back-breaking labors of the masses – the working class. A frustrated man in pleated breeches, Freder, spots a strange woman with dirty children, who apparently took the wrong elevator with an unruly mass of dirty children. She exits as quickly as she came, but Freder can’t stop thinking about her.

Next, we see the massive factory and the slave workers choregraphed to a specific rhythm. It’s at this point that we see parallels to art direction and production design in movies from the ’80s to the early ’90s. Blade Runner immediately comes to mind, as well as Ridley Scott’s bizarre and jaw-dropping commercials for Apple. Freder asks his father why they must treat their workers so badly. His father has no answer. Perhaps it’s easier to simply reap the rewards rather than give care or consideration to those who die to construct this fantasy of superiority. I think if the workers were not made to be so passive through fear, they would have revolted years before. The movie works as a plea for constructive socialism in that regard, but therein lies the inconsistency.

A Jew converted to Roman Catholicism by his mother, Fritz Lang fled Nazi-ruled Germany for Paris shortly after meeting with Joseph Goebbels, who suggested Lang to head the UFA, despite the ban of his film, The Testament of Dr. Mabuse. Hitler and Goebbels, being film enthusiasts, respected Lang immensely*. As Lang’s Judaism was hidden at the time, they would surely have been embarrassed by that revelation. Yet Lang explicitly preaches the tenets of modern Socialism, at least our perception of Socialism in the words of Marx: “From each according to his ability, to each according to his need.” Marx considered Capitalism to be the enemy of Socialism to such a degree that he also wrote (somewhat flippantly), “The last capitalist we hang shall be the one who sold us the rope.”

Freder rebels against his father after witnessing firsthand the cruelty of his father’s indifference to the plight of the workers after a fierce explosion kills several of them. Meanwhile Freder’s father approaches inventor (and early rival) Professor Rotwang (resembling a slightly bent-out-of-shape Rip Torn) with a series of old maps found among a dead worker’s possessions. Rotwang abducts Freder’s mystery woman and makes an android version of her, in an effort to discredit her with the workers she herself incites to rebellion with Freder. When Freder sees his father with this android version of his dream girl, he flips out, figuratively (but with visual flair) descending into his own personal Hell. He takes to the bed while Rotwang shows off his new creation to all the muckety-mucks with a surprisingly erotic, pre-Code interpretive dance.

Brigitte Helm’s android provides us with a delicious sneer and a winking eye on her face to indicate that she is not human. She incites brawls among the workers, as the leaders and organizers have realized the best way to destroy any notion of dissent through community is to make the workers fight each other rather than the establishment. I see parallels in modern politics and sociology occurring even now. She encourages the workers to destroy the power station, which will cause their own homes to be flooded. In the end, all that remains are desperate, hungry faces, and destroyed machinery and the workers decide that Brigitte Helm is the cause of their misery so they decide to burn her at the stake. The flames burn away at her flesh-like draping, revealing the robot beneath.

Underneath a startling examination of the human condition, Fritz Lang has constructed the definitive science fiction experience. Revelatory and exciting (as with Lang’s M made four years later), Metropolis is less an expressionist piece, and more emotional because of his reliance on character motivation rather than the static interpretation of films produced at the time. The movie is less concerned with progress than it is with entropy and the breakdown of society. Several versions of Metropolis had floated around for years after Moroder’s 1984 release, with runnings times varying from the accepted 83 minute running time to over 2 hours. Moroder, often credited with popularizing disco music in the States, suffuses his Metropolis with songs from popular artists of the time, ranging from Billy Squier and Freddie Mercury, to Pat Benatar and Adam Ant.

Critics savaged this version of Metropolis at the time of it’s release. It was even nominated for two Razzie Awards, Worst Original Song and Worst Musical Score. As this was the only version of the film I had been exposed to (also heavily promoted on MTV), I accepted it as the definitive version. Moroder’s intention was to contemporize the film and the subject matter for young audiences with the use of popular music, and he succeeds. Critics then (and now) never seem to place films in the context of when they were made, and only review them favorably if they are viewed as some subjective definition of the word, “timeless.” Though I doubt filmmakers would ever admit to it, and based on many music video produced, such as C+C Music Factory’s “Here We Go (Let’s Rock & Roll)” and Madonna’s “Express Yourself,” Giorgio Moroder’s Metropolis was enormously influential.

*Conflicting reports state Hitler and Goebbels were aware of Lang’s Jewish background, and were prepared to make him an “honorary Aryan” because of their admiration for his work, and Metropolis in particular. The film could be seen as a rallying cry for desperate, impoverished Germans after the end of the first World War. Lang’s wife at the time, Thea von Harbou (Metropolis’ screenwriter) was alleged to have been an early supporter of the Nazi Party.

Thanks to Geno Cuddy for supplying the source copy of Metropolis for this review.

Our first cable box was a non-descript metal contraption with a rotary dial and unlimited potential (with no brand name – weird). We flipped it on, and the first thing we noticed was that the reception was crystal-clear; no ghosting, no snow, no fuzzy images. We had the premium package: HBO, Cinemax, The Movie Channel, MTV, Nickelodeon, CNN, The Disney Channel, and the local network affiliates. About $25-$30 a month. Each week (and sometimes twice a week!), “Vintage Cable Box” explores the wonderful world of premium Cable TV of the early eighties.