“The Ruling Class, 1972”

“The last time I was kissed in a garden, it turned out rather awkward.”

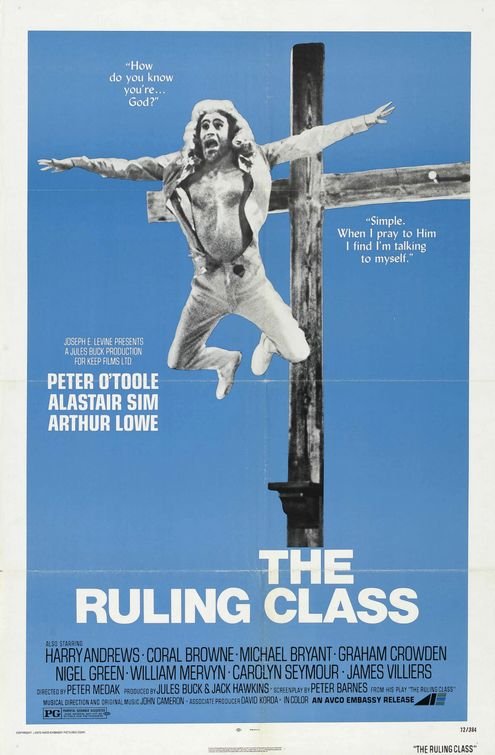

The Ruling Class, 1972 (Peter O’Toole), Avco/Embassy

The English system baffles me. From what I was led to believe, it has the more Socialistic financial trappings of most of Central Europe (even revising those standards in their entry to the E.U.) while retaining a matriarchy to keep up royal appearances and requiring heavy taxation of it’s working classes. Meanwhile, there is a Parliament; work-a-day politicians who keep the trains running on time and sustain a cock-eyed benevolent fascist dictatorship. You have to wonder how the well-fed higher-ups control this ridiculous England without losing their minds. In Peter Medak’s equally ridiculous satire, The Ruling Class, we are given an approximation of an answer: they have lost their minds. In the first few minutes of the film, one such man, the 13th Earl of Gurney (Harry Andrews) wears a variation of his uniform with the important modification of a dancer’s tu-tu and hangs himself.

At the reading of his revised will, his friends and enemies are horrified to hear that the estate will be passed on to his son, Jack (Peter O’Toole), who is also cousin to the Queen. Upon his announcement and arrival, Jack enters dressed as Jesus Christ, with robe, long golden locks, and beard, but it isn’t that he is merely dressed as Christ. He believes he is Jesus Christ. Though he locks horns with his Church of England relatives, an examiner diagnoses Jack as a paranoid schizophrenic. Hilariously, when asked how he knows he is God, Jack simply states that when he prays, he discovers he is talking to himself. His transformation is no different than the proverbial red-headed stepchild’s journey home to inform her family she has discovered Scientology, but since this is a young man of royal stock and lineage, poised to inherit an unimaginable clutch of power and privilege, his family agrees he must be destroyed for the good of the Crown.

Trading off one set of bizarre rubrics for another and unleashing hypocrisy in the form of off-putting musical sequences isn’t enough for Peter Barnes’ irreverent stage play (which he also adapted for the screen). When Jack insists his doctrine will be one of peace, charity, and love (What would Jesus do?), he puts fear in the hearts of the dogged politicians who really only want his power and wealth. They scheme to distract him with a woman (beautiful Carolyn Seymour as Lady Grace) who, with all her might, attempts to seduce Jack, but is instead seduced by Jack. She falls madly in love with him. It’s interesting how Jack (Jesus Christ) invents and improvises his belief system. Apparently it’s fine for our Lord and Savior to take a wife in Jack’s twisted interpretation. Whatever. I’m an atheist, but it’s quite charming to watch Seymour and O’Toole indulge in an impromptu rendition of “My Blue Heaven.”

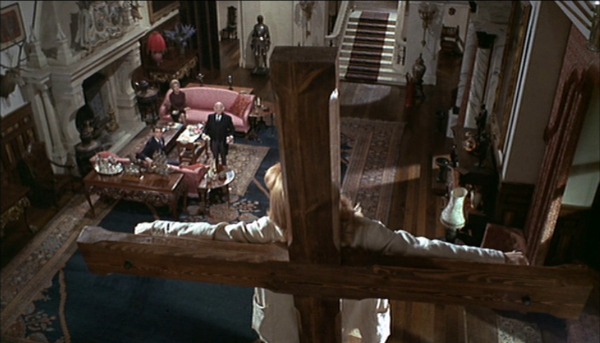

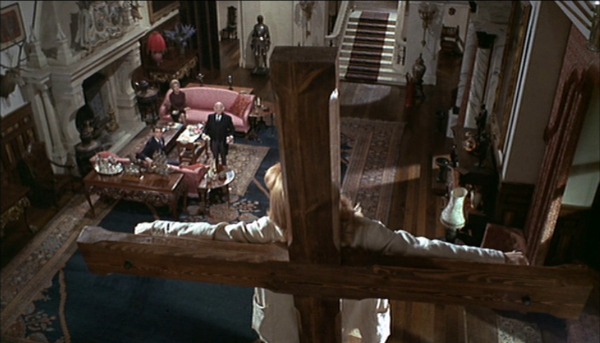

When the dimwitted Dinsdale tries to alert Jack to his family’s treachery, he violently withdraws, sensing his strategically constructed walls of illusion coming down. As much as Jack wants (needs) to be Jesus Christ, and though he hangs from a fabricated crucifix in times of insecurity, he would never bring himself to strip to nakedness and pierce his flesh with nails. He marries Grace in an empty cathedral. At the reception, Jack puts party hats on all the miserable nobles. This is where the movie succeeds: as a tarring, jarring rebuke of the affluent – those who merely inherit their privilege and execute nothing of use with it. They are, truly, the most worthless of the world. Upon a visit to a sanitarium, he comforts the inmates with prayer and song. The examiner conducts psychological experiements. He passes a lie detector test. He then undergoes electro-shock therapy (in a method reminiscent of Return of the Jedi when the Emperor tortures young Skywalker). This sequence juxtaposes Jack’s “exorcism” with the birth of his child with Lady Grace, and it is truly terrifying.

However electrifying O’Toole is (Ha!), the film relies on his madness to carry it through the more mundane and tedious passages. Barnes is a writer in love with his words, and what The Ruling Class could’ve used was another pass at the screenplay, and more time in the editing room. Peter Medak’s direction is (perhaps appropriately) stagey, but also cold and emotionless. Maybe it’s because he shoots the movie from the point-of-view of the unlikable outsiders who view Jack’s madness as a form of eccentricity. Even after Jack is relieved of his demons, we spend nearly another hour trying to determining who he has become. He stutters, suffers Tourettes-like aphasia, and possesses murderous impulses. The Ruling Class would’ve been brilliant if the filmmakers had dispensed with the notion of shooting a stage play and instead focused on the strength of film. The aristocratic air and the manipulations of the power-mad in the film would make it an interesting double feature with A Clockwork Orange.

Our first cable box was a non-descript metal contraption with a rotary dial and unlimited potential (with no brand name – weird). We flipped it on, and the first thing we noticed was that the reception was crystal-clear; no ghosting, no snow, no fuzzy images. We had the premium package: HBO, Cinemax, The Movie Channel, MTV, Nickelodeon, CNN, The Disney Channel, and the local network affiliates. About $25-$30 a month. Each week (and sometimes twice a week!), “Vintage Cable Box” explores the wonderful world of premium Cable TV of the early eighties.