Review: The Menu (2022)

“And now our final dessert course is a playful twist on a comfort food classic: The s’more. The most offensive assault on the human palate ever contrived. Unethically sourced chocolate and gelatinized sugar water imprisoned by industrial-grade graham cracker. It’s everything wrong with us, and yet we associate it with innocence. With childhood. Mom and dad. But what transforms this fucking monstrosity is fire. The purifying flame. It nourishes us, warms us, reinvents us, forges and destroys us. We must embrace the flame. We must be cleansed. Made clean. Like martyrs or heretics, we can be subsumed… and made anew. I love you all!”

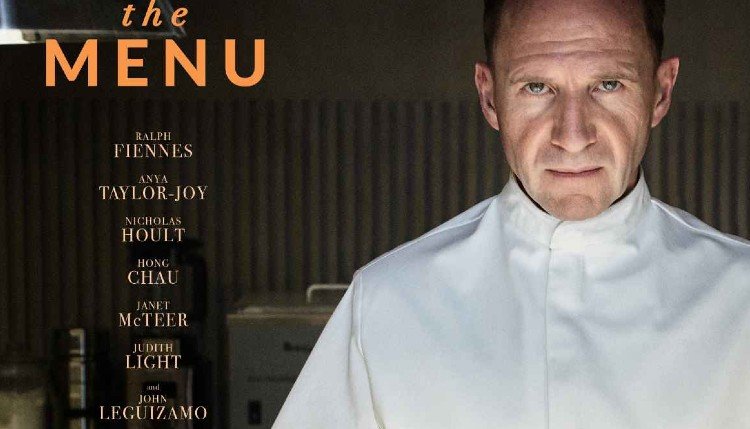

The Menu, 2022 (Ralph Fiennes/Anya Taylor-Joy) Walt Disney Studios Motion Pictures

Remember revenge? The dish that is best served … cold … it is very cold … in space … Khan? The Wrath of … well, Khan? It was a Klingon proverb. There was a meme going around for a few years about how ice cream is revenge because ice cream is best served cold. I hang out in various Star Trek circles, so I get to see all of these memes before you can see them. Aren’t you glad? Anyway … The Menu! I went into The Menu knowing it would be a variation on a popular theme these days, which is “Eat the Rich.”

Not literally, of course, but in a sense stealing their curious powers by way of revenge. The phrase, “eat the rich” is attributed to Jean-Jacques Rousseau. He said, “When the people shall have nothing more to eat, they will eat the rich.” I don’t see how that is possible. The rich tend to have security guarding their bodies. The rich have gates. The rich have islands. Celebrity chef Julian Slowik (Ralph Fiennes) has an island; an island and a restaurant on that island.

His customers are chosen and then shuttled (by way of a boat) to the island to dine on his exclusive cuisine. Slowik has the power of a deity; a hypnotic hold on his clientele. He provides a menu, but his staff carry out his orders as if they were members of his cult. Slowik’s staff issue instructions to his customers and the viewer, and we as viewers (as well as Anya Taylor-Joy’s Margot, the viewer’s surrogate) immediately take issue with the rewritten hierarchy.

We talked about the dish of revenge being best served cold, but there’s another proverb about the customer always being right. Unfortunately, these customers, even if right, are required to face down the mindless drones of Slowik’s staff as they brandish very sharp-looking kitchen knives. Fiennes’ Slowik is an intimidating presence, but (and this was very interesting) he was only intimidating to specific people. Margot’s vacuous date, Tyler (Nicholas Hoult), for example. Not the food critic, Lillian (Janet McTeer), who gave him his first (bad) review, or Margot herself.

I think Slowik had been working toward this singular event ever since he became a celebrated chef. Near the end of the movie, Margot, left to her own devices and searching for a radio with which she can arrange a rescue, finds a picture of a youthful Slowik at his happiest: flipping burgers in a diner. She puts it together fairly quickly that Slowik is miserable. That all of the joy and love had been sucked out of his life by preening elites and sycophants, as well as creditors and critics.

It’s akin to the idea that art should have no purpose but to express or evoke an emotion, and when that art becomes corporatized, it robs the creator and his audience of individuality and interpretation. Somewhere down the line, Slowik’s passion turned into a dead-end, time clock-punching job. In order to execute some kind of perfect revenge fantasy, Slowik assembles a guest list of everyone who had done him dirty over the years, from the aforementioned food critic to his corrupt creditors, as well as a curiously nameless has-been actor (John Leguizamo) and his young assistant (who has a name, Felicity) played by Aimee Carrero.

Unfortunately, there is a monkey wrench thrown into his meticulous plan: Margot. She was brought in as a last-minute replacement, and is told in no uncertain terms by Slowik that she’s not supposed to be here. Maybe halfway through the movie, Slowik informs his guests that they’re all (including him and his staff) going to die. He asks Margot if she wants to die with him, or die with the guests.

Margot constructs a remedy for Slowik that will not only bring back his joy of cooking but also save her life in the process. She tells him she’s still hungry, and then she dares him to cook her a cheeseburger. He dutifully obeys, making a cheeseburger so gorgeous it made me hungry even after I finished eating my dinner. That particular night we had ravioli, meatballs and sauce with garlic bread on the side. I was compelled to reveal my menu because that’s what the movie does with each course, almost like a chapter stop on a blu ray menu.

Margot can’t finish the burger and asks if she can take it “to go,” thus securing her escape from Slowik’s mad island. Slowik, for his part, capitulates as he prepares dessert, which involves dowsing his guests with graham cracker crust, chocolate sauce, wrapping them in marshmallows and setting fire to them as human s’mores. We get into Midsommar territory with this final course, but thankfully it doesn’t become a heavy-handed treatise on Wicker Man-like murderous femininity.

As Margot eventually escapes on a boat and finishes her burger, she watches the island burst into flames. One of the reasons The Menu works compared to something similar (say … oh, I don’t know, Glass Onion?) is because Seth Reiss and Will Tracy’s script (from a story by Tracy) doesn’t rush to make the audience hate their characters, nor do the characters exist as early 2020s archetypes/sociopaths, as well as mixing in a likeable heroine in Margot. The script even manages to foster sympathy for Slowik.

The Menu summons two separate ideas. It’s a black comedy in the tradition of Parasite, Bong Joon-Ho’s brilliant analysis of class in South Korea. The other idea is Jonathan Swift’s Directions to Servants, an inane set of instructions from “betters” to their “lessers” that get progressively ridiculous once the reader becomes aware just how much more vulnerable the wealthy are than those who serve them. The “eat the rich” philosophy works with both ideas, and The Menu is easily the best film of 2022.