“Urban Horror: The People Under the Stairs and Get Out”

I wonder where Jordan Peele gets his ideas. Don’t you? It’s like looking into a window of nostalgia (as far back as his generation will go) to dredge up those pieces of the pop-culture gristle and squeeze enough juice out of those pieces to create a new phenomenon. He’s an enormously talented comedian, writer, producer, and director, but there isn’t a balance to his sensibility to label him a “comedic genius” or “master of horror.” I like Jordan Peele, but I don’t know what he’s trying to do. I can say that. I can plainly say that.

Give us a greater idea of your talent, Jordan! I know there was Key & Peele, the Comedy Central sketch show, but in my day, we had Dave Chapelle for subversive racial humor. I know there was Keanu, a stupid yet incredibly funny movie about two very white (but “blackish”) friends who endanger themselves to find a kitten who has been snatched up by belligerent drug lords, but in my day, we had Harold and Kumar Go To White Castle. I know there was Get Out, a Stepford Wives pastiche that aims to indict lazy white liberals who seek to re-program black people.

I think Jordan Peele has a sensibility. He diverts expectations and surprises audiences with a juxtaposed view of the cultural marriage uniting sociology and racial politics. A couple of weeks back, I had to look at Wes Craven’s 1990 “urban”/horror movie, The People Under the Stairs, for the Upstairs at Froelich’s podcast. It was a show about Wes Craven, so we also had to look at The Serpent and the Rainbow. The People Under the Stairs was the superior movie, but we enjoyed both. All through the movie, I was thinking, “This is what Jordan Peele tried to do with Get Out, but he failed.”

Why did he fail? That’s a harder idea to parse than anything else I might’ve been pondering at the time. There is the grand spectacle of statement. Jordan’s trying to make a statement here. He’s trying to teach us something. This is a “teaching moment!” Everybody shut up and watch the movie, absorb it and let it seep into your skin. All through Get Out, I felt like I was being lectured to in a very condescending way. These were the early, halcyon days of white privilege when we didn’t know just how good we had it! Everybody’s respectable in the movie.

The best performer and player in the movie is not Daniel Kaluuya. The best performers are not Catherine Keener or Bradley Whitford as the husband-and-wife team of brain-transplanters bent on racial domination. The best player in the movie is Lil Rel Howery as Rod Williams, TSA employee and no-nonsense hero who arrives just in the nick of time to rescue Chris Washington from his psycho girlfriend and her family. The whole thing smacks of conspiracy, just as The People Under the Stairs did.

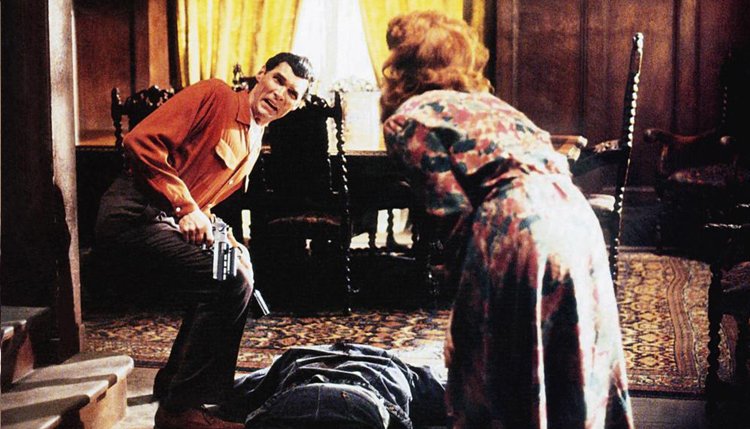

The People Under the Stairs is a different movie. Brandon Adams’ “Fool” character is an observer of absurdity. Twin Peaks’ Everett McGill and Wendy Robie are a murderous cadre in a world where their actions would be deemed horribly illegal. “Fool” becomes a hero when he decides to save the imprisoned people in the basement. In the world of Get Out, all the white people wink and nod at each other and share the secret of their conspiracy. Chris Washington is not about saving anybody but himself when the truth comes out.

It’s been argued by some that Get Out is actually a subversive comedy, and we shouldn’t take any of this seriously. Get Out is not a comedy. It is not structured, nor edited as a comedy. It is structured as a horror movie, and while both genres depend on some degree of subjectivity, Get Out mines thrills and blood-curdling terror instead of cheap and easy laughs or irony. Lil Rel gets a laugh at the end of the movie, the biggest and broadest laugh, but I believe that laugh was meant to cut the tension, not make us feel any semblance of positivity at what we’ve just watched.

I think Get Out is a grand and glorious statement from a filmmaker I can’t quite comprehend; a filmmaker who would then go on to make Us, a $20 million dollar movie that made $255 million, but is not a comedy film. He followed Us with Nope in 2022. As the budgets go up, the box office goes down. Horror movies can have a sense of humor. Wes Craven’s were often imbued with a sense of humor owing to his clever story construction and dialogue, and he could work within a budget.

I think Wes Craven was always invested in horror because he wanted to embrace the absurd without directly confronting it, like Kubrick with Dr. Strangelove. He had one excursion away from horror with Meryl Streep and Music of the Heart but after that, he quickly went back to horror. He didn’t care for the critical accolades, perhaps realizing critics are a force of nature, complicated shifters of attitudes, and disposable, angry, frustrated writers (like me!) who mean nothing in the grander scheme compared to movie-loving genre fans.

They love you one minute. They hate you the next. That’s the nature of criticism. Criticism shifts to the moral paradigm, the morays of the moment. A critic from a hundred years ago will think you’re going too far, and a critic today will tell you you’re a prude. Craven never addressed his critics publicly, even in the days of Last House on the Left, a movie that engendered incredible controversy upon release in 1972; viewed as exploitation (of course it is as all consumed entertainment is exploitation) and viewed as tasteless and vile.

Movies are made to be seen. They’re not made to provide social or political commentary. If they are, they cease to be entertainment and become propaganda. I’m not saying Peele’s Get Out is propaganda. It is most definitely exploitation, and it does entertain, but not on the level of The People Under the Stairs. I think Peele consumed everything; all culture, all world, all movies, all television and then he regurgitated what he enjoyed through his eye.

I’m reminded of Cheryl Boone Isaacs in 2015 representing the Academy of Motion Picture Arts & Sciences admonishing the ticket-buying public to believe that a filmmaker (or the “filmmaking community,” whatever that is—there is no community) has “a responsibility.” She couldn’t be more dead-wrong. Filmmakers serve the audience. Filmmakers have “a responsibility” to the ticket-buying public to entertain them. These days, we’re trying to pretend that’s not true, but it is, and always has been. If you want blood, you’ve got it! Are you not entertained?

Boone Isaacs’ statement reads like a warning; that there must be a set of accepted criteria, a list of rules for filmmakers, and “social responsibility” is at the top of that list, but because movies elicit subjective responses, no one person will ever agree with another person’s assessment of either “entertainment factors” or “social responsibility.” Case in point: last night, I watched a movie that received a 98% rating on the Tomato-meter and 81% audience approval rating. The lead actress got an Academy Award nomination. I thought the movie was complete crap; not worth the hard drive on which it was captured. Everything about it was wrong. The movie did not entertain me.

Who is right in this situation? No one. Not one person. The groupthink has gotten worse in the intervening years, as some members of the Academy are calling Joker, “irresponsible.” How is a movie irresponsible? I didn’t have a title for this piece, so I had to call it “Urban Horror,” even though both movies are not urban, by any stretch of the imagination. Both movies take place out in the “weeds,” as it were; isolated, planned, homogenous communities. I think we get one scene in a tenement in The People Under the Stairs. We see Daniel Kaluuya’s tastefully-appointed apartment in Get Out, but there’s nothing terribly “urban” about these movies.

When I think “urban horror,” I think Michael Winner’s The Sentinel from 1976, or Rosemary’s Baby, or Ernest Dickerson’s Bones from 2001. Get Out is about as urban as The Amityville Horror. I think “urban” is an overused (at this point) colloquialism meant to indicate the predominant race or skin color of the people involved in the film. There was an “urban” section at the local Blockbuster Video when I was a kid, same as there was an “alternative lifestyles” section,” indicating movies with homosexual themes. Urban themes might be at play and that’s what makes both movies enormously interesting as well as entertaining, even if they were made for very different reasons.

Today, the idea of “subgenre” is dead, as most, if not all, movies are required to fly the colors of diversity; a calling card to let audiences know the makers of these new films are “woke.” I’ve tried to view this pop-culture change with the eyes of history, noting that everything manufactured is a product of its time. These ideas come and go in cycles. Who knows what will be the next big thing? Wearing your hair a certain way, or maybe evening gowns will come back in style? Maybe we’ll be able to tell women they’re beautiful again? Whatever happens, I just hope soul-patches and shoulder-pads don’t come back.

Happy Holidays everyone! It’s good to be home again.