“The Sliced-Up Pear: Two Suspirias”

What is a world except a delicate thing no one can understand? Is this a world of frozen eyes, the smell of mold, the rusted spring sticking out of the ages-old sofa? There is a directionless young woman with brown hair speaking in broken phrases. She has an unnerving baby voice and she consults with someone who is probably a therapist. There is something off about the therapist.

The young woman speaks quietly about “perfect balance,” and about how “they took her hair, her urine, and her eyes, and now they can see.” There’s still too much dust to make sense of this. Suspiria has a smell. It’s a smell of black ink, the iron of blood, that troublesome mold. The new Suspiria proudly proclaims a structure of six acts with an epilogue and tells the story in a “divided Berlin.” Fine.

I thought you could tell the story anywhere. Berlin. Rome. Honolulu. Duluth. It doesn’t matter. The one component I had become intimately familiar with in the journey from convoluted art house narrative to screen was Thom Yorke’s incredible score. Several rotoscope-like music videos had been released to YouTube in the months of lead-up to the premiere.

Director Luca Guadagnino wants to paint a top-coat of misery on top of his shattered sculpture by placing the action in the center of failure. His Suspiria is a topography of unclaimed land, infertile soil, rusty cages, and a rain-soaked Berlin wall inside a slum-like enclosure. It wasn’t necessary to have filler so early in the movie, but we’re being held against our will. Unlike Argento, this is an anguished soul, not an orgasmic splatter of blood.

It doesn’t completely work, and I will explain why it doesn’t completely work. Dakota dances in preliminary audition for her masters. She’s very nearly completely wrong for the part (and this dance class) as she doesn’t have a proper body for dancing. As a child interested in dance, she would’ve been told this years ago, but she is an actress playing a part.

This is an unkind and deceptive industry that sells the wrong dreams to children. Not everyone can be a dancer. I’ve known them. I’ve seen them fall. I’ve seen them fail. Dakota is a child’s fantasy. It makes sense of what we ultimately learn about the Tanz Akademie (inexplicably rewritten as Markos in the remake), but not in the context of keeping to some form of reality in any dance school. This is the delicate world we cannot understand.

We know one or two things. We know the world of dance is cruel. We know entertainment destroys its children. If you are Guadagnino, you want to combine disparate elements of the cruelty of dance with the heart of the supernatural. You’re going too far. You’re straying off the page, off Argento’s path. Why are you doing this?

We don’t need half the items he gives us. Why does he give them to us? As I continue to ask the question, I keep being led off the path by Thom Yorke. His score, while almost genius but in a good way, doesn’t hold a candle to the simple 12-note motif devised by Argento and the Goblins. It remains in sunny repetition just as the Goblins, but it stays inside the vehicle at all times, rather than open the doors and stretch its legs.

Rigidity is key in understanding this Suspiria. It is not free. It doesn’t billow like Argento’s movie. This rigidity wants to be seriously informed as well as seriously inform. From the outset, it appears the teachers want to drive their students mad. Isn’t that the purpose of all in positions of authority? Resounding “yes.”

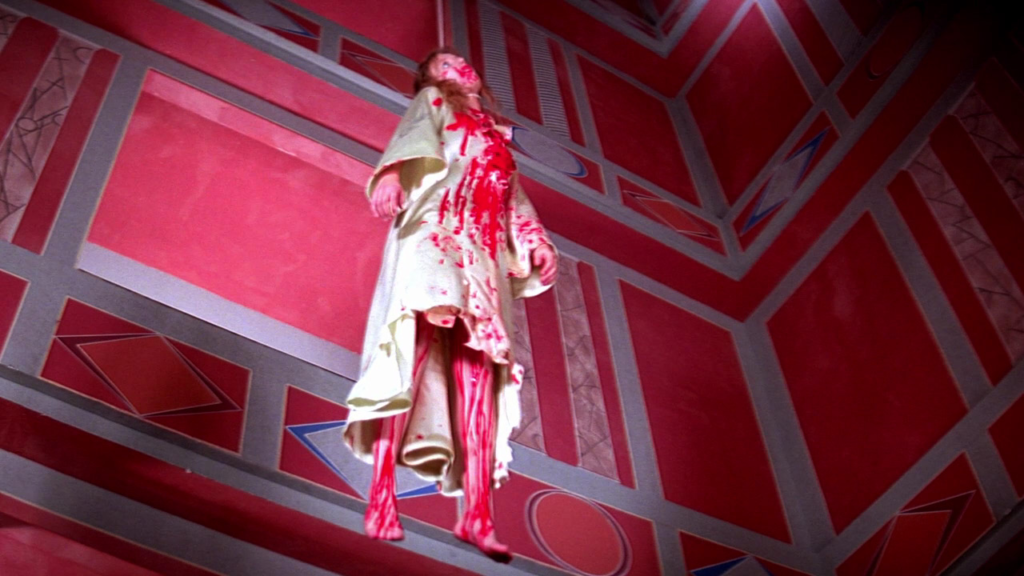

When Dakota challenges her teachers with a blind interpolation of a dance, her moves are “transferred” to an unwilling vessel, torturing her body by unreal, painful contortion. Dance becomes a cursed object, causing pain and bloody death to those unwilling to hear the music. This sequence goes on way too long, and to little purpose, except to demonstrate some level of unnatural power these teachers (and some students) possess.

I suspect this is what Guadagnino was aiming for all along; a brash body-horror juxtaposition of art with the grotesque. Dakota’s moves turn her victim into a schizophrenic sculpture; flesh in place of marble, misshapen and raped. I can’t imagine how anything else in the world matters. The scene itself is edited as dance rather than torture, which is clever, but uninspired.

The actors are contorted flecks on a white sheet of paper smeared with tantalizing syrup, like crushed houseflies. Unfortunately, the mystery is described only in a series of notes rather than the piercing cries of young women in the din of loud and violent rainstorms. We could do a little more in terms of our storytelling without the need for these inappropriate handwritten notes.

The dialogue that isn’t in service to the story is one of the remake’s strengths.

Tilda Swinton is another. She completely disappears twice inside the film, under makeup and wardrobe. Her voice is an instrument, a rarity in actresses these days. Close your eyes and try to determine if either Dakota or Chloë Grace Moretz is speaking. Try to even spot them in the dark photography. You can’t. I wouldn’t have known Moretz was in the movie if I didn’t see her name in the titles.

You can hear Tilda. You can see her with her distinctive features. She has a voice, as off-putting as her action. Monsters figure favorably in this remake as well, but unlike the original movie, we aren’t sure if we’re dealing with the ages-old coven of witches, or simply those with severe emotional disorders who resort to self-mutilation.

There are so many inappropriate jump-cuts to be digested, smears of blood and broken mirrors, that I believe Guadagnino is attempting to make something seem more important than it actually is. This is a fault of many making films these days. The running time is unforgivable, especially considering Argento’s lean one-hundred minutes.

A movie isn’t made these days with a thought toward editing to something sufficient in telling the story, but instead every movie goes overboard in nailing premises and hammering them home over and over again until even the most simplistic story gets a three-hour running time. Suspiria comes close. The color is depressingly muted, unlike Argento’s violent blue and red painting.

The production design is virtually non-existent save for the ever-present walls of mirrors you always find in a dance studio. Every room in Argento’s film looks like it belongs in a different house. There are ideas that linger. Dance. There’s much more dance. Weirdness. There is much more weirdness. Weirdness for the sake of weirdness. Not in the fun, Lynchian way, but … disappointingly self-important as with all modern cinema.

There are too many characters dancing around when in the original, Jessica Harper was sufficient. Making her the locus of the story, as well as our surrogate holds our attention much more than the handful of students (among them the brilliant Mia Goth from the X/Pearl movies) serving merely as place-settings for Guadagnino’s sumptuous banquet.

Think about the coven of witches and demonic forces inside a ballet school. These two images should be the only items that matter. Harper is a sickly Nancy Drew uncovering the blanket to reveal the maggots on the meat. The original Suspiria conjures images of maggots, broken glass, barbed wire, and inhumanly red blood.

Harper has the story-driven advantage of being a stranger in a strange land, giving everybody else the necessity of xenophobia, and it’s a perfect note with which to dance. In the remake, everyone is … strange. Too bad. These aren’t songs. These are hymns. Same meter, different words going on at length for pages and pages, and by the time of the final measure, the singer forgets what he or she is singing. They forget what story they are telling, yes … Suspiria.

I have to wonder if the remake has been forgotten, and now the title will only refer to the original movie. Tilda makes Dakota jump higher and higher repeatedly. Why? What purpose does it serve, except that Dakota has become properly house-broken? In the next scene, a woman seated at a dinner table inexplicably draws her steak knife and plunges it into her neck repeatedly.

If the intention was to demonstrate the power and the hold the teachers have over their prodigies, the message was received long, long ago. All that finally remains is the bizarre act, a mishmash of dance and satanic orgy? Your typical monster mash has common structure; the same as anything that tells a story. Introductions all around. The girl with the long, brown hair.

Troubled but determined. Looks at her slashed, bloodstained hands and seeks some comfort from strangers soon-to-be-friends. I feel the trouble, but then it dissipates. The story flashes back to an earlier time, and we’re still not oriented. There is the feeling of time travel and hidden motives. This isn’t just a witch older than God and her demon looking to inhabit a newer, younger body.

Critics, at the time of the remake’s release, dredged up shared themes of motherhood. Motherhood? Maybe. Witches of folklore and horror movies are not mothers in the classic sense. They consider themselves mothers in the New Age and wiccan sense of the word. Gaia, ancestral mother, Earth Mother, mother of all life.

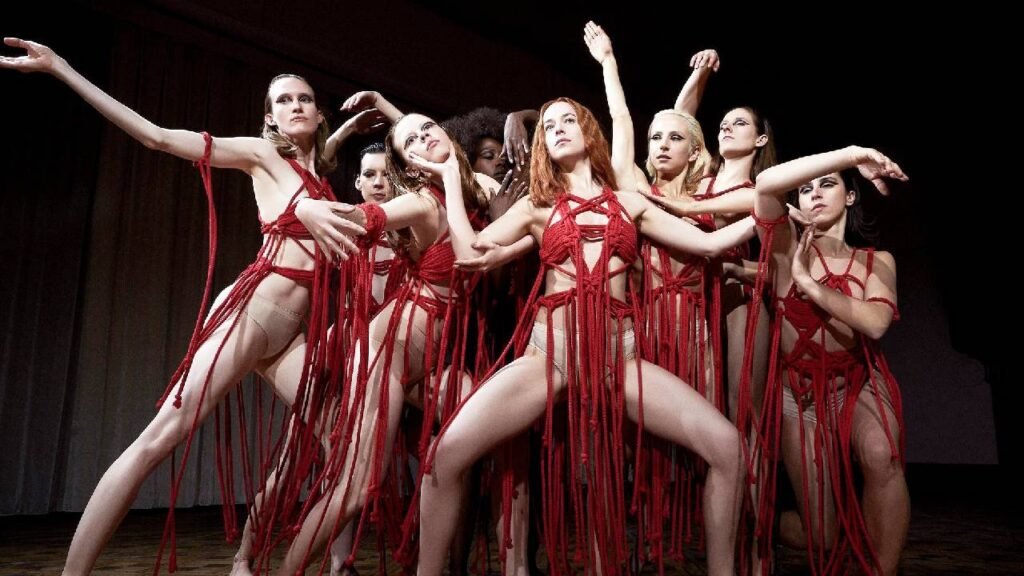

From what I know of the modern wiccan, there is nothing in this movie that resembles or even deigns to pay respect to those practices. Indeed, after the centerpiece is revealed, that of a “graduation” performance, an incredibly schlock-ridden blood orgy is conducted with the dancers, all stripped down to their skin, pleading for death’s release from the newly ordained Mother Suspiriorum.

Only a few are spared after the festivities. We have to have some students to have a dance academy. It’s odd how not-creepy this supposed horror film is. There isn’t one deliberate off moment in all of the two-and-a-half hours of the movie’s running time. Not one moment designed to send shivers down your spine.

The film is all spectacle, just as in the enormous chamber where the sacrifices are made. In Argento’s movie, Harper’s roommate is menaced by a cloaked, hooded murderer stalking dripping, shadowy halls. She eludes the killer, room to room, until she stumbles into a room filled with barbed wire. The wire takes it time slashing through her skin, and the killer finishes the job. The school goes into cover-up mode to explain away the sudden disappearances of Harper’s classmates.

There is a mystery to be had. The remake’s scenes don’t follow. They simply exist in the spaces between a character’s pause, from écarté to effacé, without showing us the body’s motion between those positions. It is more interested in beginnings of stories than any rewarding, or at least satisfying, resolutions.

The only resolution we are privy to is in the story-bow neatly tied up from the beginning. The directionless young woman with brown hair speaking in broken phrases. The unnerving baby voice. The therapist who has offered her shelter. This is when we discover she is not the student anymore but the teacher. Mother Suspiriorum. The ages-old witch and leader of a coven that has seen time erase itself. She’s seen war and death over the course of centuries.

She tells the therapist she knows what happened to his wife, Anke (played in dream sequences by Jessica Harper herself—I thought it a nifty cameo). She died of exposure after twenty days in a concentration camp. “She was not afraid,” she tells him. “Her thoughts were of you. Only of you.” The dressed-up schlock of the previous two hours disappears behind this thin veil of conscience and an understanding of true horror; human horror.

The script, as written by Dave Kajganich opens with an interesting quotation attributed to Joseph Goebbels in 1937:

“Dance must be cheerful and show beautiful female bodies and have nothing to do with philosophy.”

Nothing can replace sheer human misery, human tragedy, human suffering, human monstrosity. All we know is what we are, and it rings disturbingly true and familiar. We know our kind. We don’t need witches. We don’t need vampires. We don’t need enemies and boogeyman because we are the sum of our horrors. We are Goebbels, and we are Jesus Christ. We create God to deny God, and we do the same with the Devil.

The final scene of Argento’s movie has Suzy Bannion stab the glowing shape of Helena Markos, causing her coven to go mad and set fire to the dance school. Harper smiles as she exits the school and we’re left with the cacophony of their screams as they burn to death. In Guadagnino’s opus, there is no ending other than the knowledge that evil knows no master and lives on forever.

There’s nothing to be seen of an antidote; a dose of religion, the presence of God. This is 1977 Berlin, and a wall has been put up perhaps to block the nation’s collective madness, the time when they turned their backs on humanity, but that madness might still feel the presence of God. We’ll never know because this is the end of Suspiria.

After Mother Suspiriorum shares her secrets with the doctor (also played, stunningly, by Tilda Swinton), she seems to erase the memory of what she told him, as well as any memory of a wife. She goes away, perhaps to open the dance school to new applicants. The script ends with the last sentence: “A wife, a life, an entire war, have been forgotten.” This Suspiria is not a horror film. It is a visual record of atrocity using a horror film as its sheep’s clothing.

The directionless young woman now has purpose. That is the new Suspiria. I did have questions with regard to the conclusion of Argento’s fantasy. The smile on Jessica Harper’s face. What was it? If I were to narrowly escape the burning cauldron of a demonic dance institute, I don’t think I could muster anything even remotely similar to Harper’s self-satisfaction … unless …

I don’t know if it was in the script, but maybe he whispered something to the young actress. Maybe he told her what we come to understand in the remake: evil knows no master and lives on forever. Still, the fiery choice at the end of the movie brings closure whereas Guadagnino and Kajganich want us to know that nothing of reason will survive.

Which ending do I prefer? I enjoy the hollow flames, but I also understand the inevitability of monsters. Religion can make a man whole, but reality will make him strong. Suspiria can be both. Suspiria is both, but the remake’s running time and Pinteresque pauses between scattered pieces of dialogue make it a frustrating experience. Horror should not frustrating, and it should not dance in ambiguity.