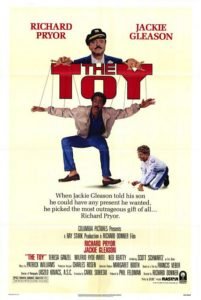

Vintage Cable Box: The Toy, 1982

“If you want a friend, you don’t buy a friend, Eric, you earn a friend through love and trust and respect.”

The Toy, 1982 (Richard Pryor), Columbia Pictures

Jack Brown (Richard Pryor) is a frustrated writer who can’t seem to find work. What? Is this 2016? He insists to anybody who will listen, “writing a book is a job!” He happens to be right, but as we know, the writer’s “market” is nothing more than a speculative proposition with no guarantee of gainful employment or steady paychecks, and also everybody with a personal computer these days thinks they’re a damned writer, so they sap the market with badly written, terribly edited folderol. To save you a trip to the Googles, folderol means “trivial or nonsensical fuss” – you’re welcome. He’s about to lose his house, and his idealistic crusading girlfriend urges him to find any kind of employment to keep the house.

He applies for a job at U.S. Bates Industries, and while Ned Beatty (as the chief hiring executive) is amiable enough, he bristles at Pryor’s qualifications (the fact that he is overqualified). After Pryor warns Beatty about his litigious lady, Beatty finds him a position as a “cleaning lady”, in which he has to ridiculously wear a maid’s uniform in a very awkward dinner party scene. Jackie Gleason is U.S. Bates (acquaintances inadvertently call him, “you ass”), a man used to getting everything he wants. His son is of the same stock of what we would call “white privilege” today. Pryor is transferred to one of Bates’ department stores in another cleaning position capacity. His unusual child-like nature, curiosity, and propensity for causing chaos appeals to Bates’ son, Eric (brat Scott Schwartz, last seen in A Christmas Story with his tongue frozen to a pole). He tells his father’s underlings he wants to “purchase” Pryor. They throw cash at him, and in his position, he really has no choice, right? If somebody is paying you to be a character in a child’s fantasy, you take the money!

They seriously put Pryor in a crate and ship him to the boy’s house. Pryor, for a good portion of the running time in this movie, seems to be nothing more than a human chess piece to be moved around the board of life at the rich white man’s pleasure. What? Is this 2016? I know, I already did that joke, but really how many of us can relate to Pryor’s predicament? He even calls out the requisite analogy to slavery, and this does seem like slavery. Gleason offers a comparable salary to one of his newspaper writing staff, but what Pryor wants is a job on the newspaper. Gleason tells him there are no jobs, so Pryor demands more money. Gleason relents. As expected, the child is a terrible little bastard who tortures Pryor to no end. His bedroom looks like F.A.O. Schwartz (maybe it was named after him … hmm). He’s ill-mannered, yes, but this being an 80s movie aimed at children, he just needs a little guidance and love from his father.

Wearing Spiderman pajamas, Pryor beweeps his outcast state to an assemblage of stuffed animals and other toys. He talks about how he is the wave of the future, a “wind-up asshole”, and how every kid will want a personal Jack Brown of their own. After enduring more humiliation at the hands of Eric and Bates’ trophy wife, Fancy, he decides to leave. Bates then offers him $10,000 to return when Eric cries that he has “nobody to play with anymore.” He accepts. I wonder what the real lesson of this movie is – not that children need fathers who love them and talk to them (not having a father when I grew up, even I knew that), but that people can be bought for the right price. What? Is this 2016? Third time’s the charm!

So Pryor and the little bastard bond. Sorry for all the epithets but this child is beyond therapy. He’s a destructive little thing, a mirror image of his father (a bitter man with a different set of toys), who gets everything he wants, even though what he really needs is a friend. They start up a small little newspaper called The Toy, (a kind of Street News, remember that?), when Eric tells Jack of his father’s various financial antics. He buys politicians. He supports members of the Klan. He drives poor Ned Beatty to drink when he orders him to fire a loyal employee for trivial reasons. He seems kind of evil, doesn’t he? Eric decides to discredit and destroy his father in the Media. Not exactly mainstream, but still.

Despite the mixed morality of the story, I still love this movie, mainly for Pryor. Gleason is not the thunderous comedic talent he once was (as in The Honeymooners, for example), but he has good chemistry with Pryor and graciously takes a back-seat to Pryor’s timing and negotiation of a given scene. He’s also surprisingly menacing. Pryor’s work with the boy keeps those scenes energized as well. As a kid, I enjoyed Eric’s world of toys. As an adult, I appreciate Pryor’s straight talk with the kid, as well as the racial humor. A lot of this stuff would be considered quite controversial today, but it was interesting that back in those days, we could mine the controversy while still being entertaining, and not terribly preachy.

Our first cable box was a non-descript metal contraption with a rotary dial and unlimited potential (with no brand name – weird). We flipped it on, and the first thing we noticed was that the reception was crystal-clear; no ghosting, no snow, no fuzzy images. We had the premium package: HBO, Cinemax, The Movie Channel, MTV, Nickelodeon, CNN, The Disney Channel, and the local network affiliates. About $25-$30 a month. Each week (and sometimes twice a week!), “Vintage Cable Box” explores the wonderful world of premium Cable TV of the early eighties.